As we move into Room 28, we encounter a transition from the High Renaissance to the Baroque. The Baroque period is typified by ornate details, theatrical movements, and intense drama. Here though, those characteristics have not yet taken precedence in the art featured in this room; instead, the drama is mingled with vestiges of the Renaissance. Indeed, one of the artists featured in this room, Giovanni Battista Moroni, is more Renaissance than Baroque, but he is included in this room because his ultra-naturalistic style is a precursor to that of the Baroque painter Caravaggio, whose work appears in D29.

Moroni is primarily known for his portraits of the petty nobility of Italy. He was famous for his ability to capture his sitter’s inner psychological life while still portraying his sitter’s likeness with extreme accuracy. In addition to the realism with which he depicted his sitters, the type of sitters whom he choose to depict anticipated Caravaggio’s revolutionary paintings depicting “ordinary” people. Indeed, one of Moroni’s most famous portraits, known as The Tailor (located in London’s National Gallery), depicts a working class man dressed as a gentleman, an extremely innovative depiction. Indeed, up until this time, only upper class individuals were thought “worthy” subjects of art.

Here, Moroni’s portrait in this room is of Pietro Secco Suardo, painted in 1563.

The Suardo family was one of the most important aristocratic families from Bergamo. In fact, Pietro served as Bergamo’s ambassador to Venice. Moroni included several allusions to the family: the flame is the family’s emblem and the inscription on the pillar hides the family name (ET QVID VOLO NISI VT ARDEAT?). The inscription comes from the Gospel of Luke (Luke, 12:49), which states: “I am come to send fire on the earth; and what will I, if it be already kindled?” (KJV). The minimal architecture shown inside the room highlights the architecture seen through the window. The landscape is likely the view that one would have from the Suardo family palace in Bergamo, a fitting view for Pietro who had left his hometown to become an ambassador in service of same. His status as an ambassador is attested to via his sword (indicating that he is a knight) as well as the luxurious fabrics of his clothes, which are of the in-vogue Spanish fashion. Finally, the type of portrait is known as the so-called state portrait, the most prestigious type of portrait, which displays the sitter’s full length. It became popular during the second half of the 16th century especially due to the international output of Titian, who was well-known for favoring the full length portrait.

The other artist displayed in this room is Annibale Carracci, who is an another forerunner of the Baroque style. As opposed to Caravaggio’s naturalist approach to Baroque, Caracci focused on classical forms. His figures often appear idealized, a clear rejection of the artificiality of the style known as Mannerism. So successful was Carracci’s style that he, his brother, Agostino, and their cousin, Ludovico, founded a school initially called the Accademia dei Desiderosi (“those who desire”) and later renamed the Accademia degli Incamminati (“the progressives”). In a reflection of Carracci’s style, the school emphasized nature, human models, anatomical dissections, and the works of “old masters.” One such work that demonstrates Carracci’s return to classical themes is Venus, Satyr, and Two Cupids, or La Bacchante (1587-1588).

It was considered so successful that it used to be displayed in the Tribune during the reign of the Medici dukes as seen in the top left hand corner of Johan Joseph Zoffany’s The Tribuna degli Uffizi:

The work was meant to be an explicitly sexual scene, as demonstrated by Venus’ nudity and the presence of the satyr and grapes, both symbols associated with Bacchus and unbridled sexual desire. Some scholars believe that the two cupids are actually Eros (god of physical love/desire) and Anteros (god of requited love/spiritual love). Read in this way, the painting becomes a battle scene between Eros, whose passion was uncontrolled and slightly menacing as demonstrated by Venus’ attempt to cover herself while the satyr seeks to pull the cloth away, and Anteros, who controls passion by holding onto the satyr’s horns.

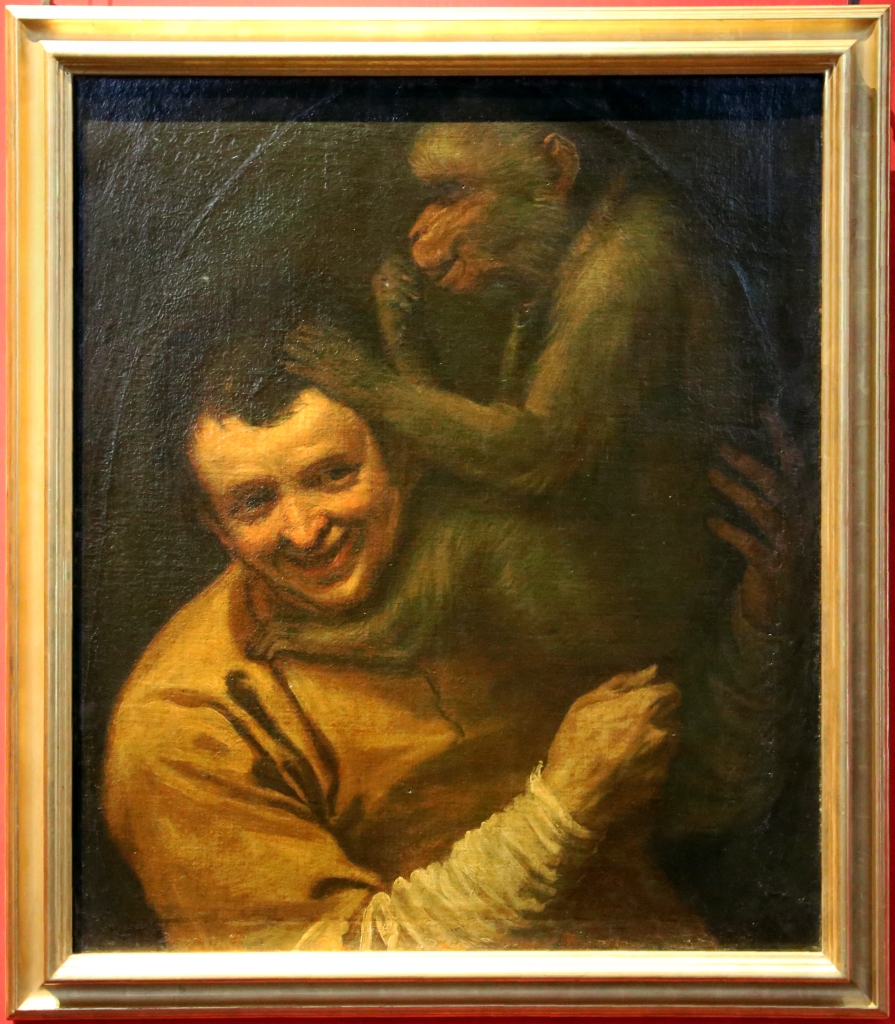

Carracci’s other work in this room is reminicent of his early style in which he tended to focus on themes of everyday life, including his more famous work known as The Bean Eater. It is known as Man with an Ape. (1590-91).

The earthen tones that he uses in this work were deemed “appropriate” for a lower class individual pictured here since colorful clothing was more indicative of upper class individuals as they could afford the dyes to create such clothing. Like Moroni, Carracci shifted “low-life genre” painting away from mocking the lower classes to actually depicting them, thereby facilitating the movement away from high classical themes, a movement which Caravaggio took to heart.